One of the great ironies of the pandemic has been one of scale: small acts of community abound and mean more than ever, even when our larger universe of social connections feels so disrupted.

Maria Reed, Director of Community Services at Westbank First Nation (WFN), has been heartened by the coming together of her community over the past months. Located in the Central Okanagan, WFN is one of eight member communities in the Okanagan Nation Alliance (ONA), comprising five Westbank community lands which are home to both WFN members and non-members. In 2020, WFN was awarded a PlanH Healthy Communities Capacity Building Grant to conduct a Childcare Needs Assessment. Part of the Healthy Community Engagement stream, the project focused on hearing from members and non-members in the WFN community towards developing a strategy to support families and children that supports existing regional initiatives.

As with virtually all communities, the task of engaging folks during a pandemic was daunting, especially when the focus was hearing from busy families juggling a constantly shifting landscape of work and school. Further complicating things, the Childcare Needs Assessment was only one of several major engagements happening at the same time, including receiving input around an updated Comprehensive Community Plan.1

“I’ve been blown away with how much engagement we were able to get,” reflected Reed dispelling any myth that engagement can’t be done well due to physical distancing measures. She attributes much of that success to engaging on what is needed in the community, not “just doing it because [you] think you need to do it.” Working with consultants from Urban Matters, WFN made a swift transition to multi-media engagement techniques, including distributing iPads to the Elders (and youth trainers!), moving information to an online dashboard and establishing a regular video update on important news from the Chief.

In the meantime, the community continued to find ways to safely commemorate important occasions. One such example is the baby welcoming celebration. While in person celebrations and events were not possible, Reed witnessed her team’s creativity to make this special moment happen for parents. They prepared a gift basket ahead of time with all of the beautiful items needed for the celebration, worked with local restaurants to have a full meal ready for the whole family, and even set up video calls so that the basket could be opened for all to see and the meal enjoyed together. Interior Health have been extremely supportive and communicative, and Reed credits her team with an indefatigable commitment to making new parents feel connected.

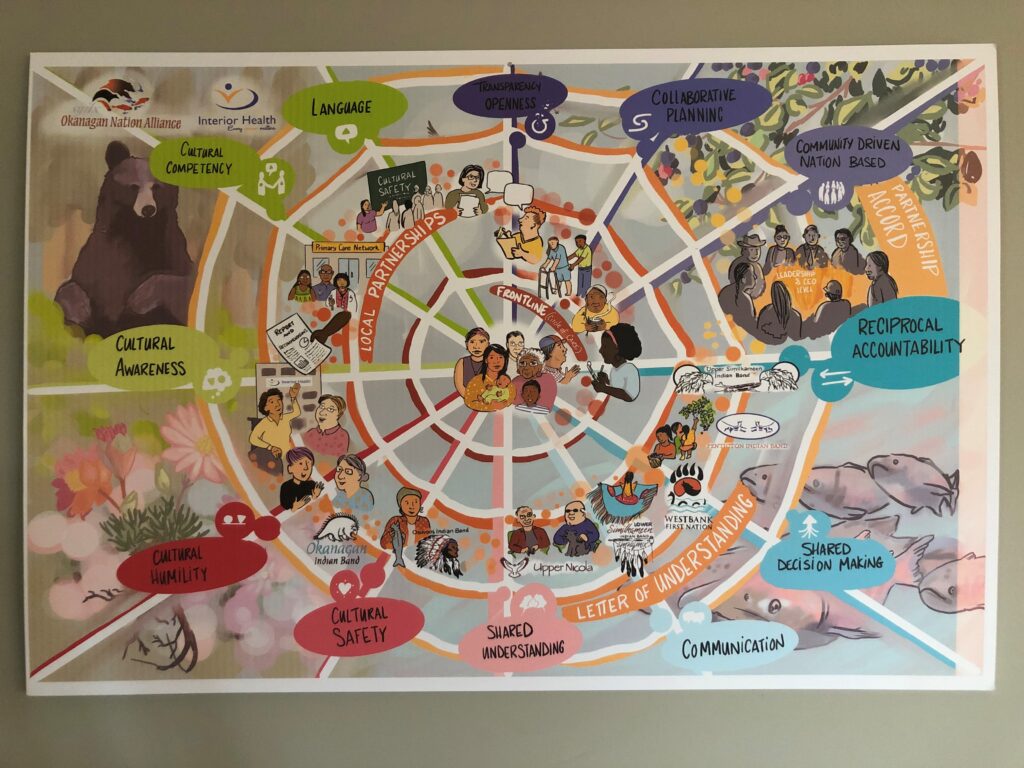

“I like to use the word nimble,” says Reed. “Things take a lot more time. It’s three times as much work to get projects off the ground, so we have to be inventive.” The nature of the pandemic has meant that the WFN team is now more collaborative than ever, reaching out across departments for support. The WFN Community Services team uses the analogy of a spider web, expressing that the client or person is at the centre of the web, with many strands being held by many hands. In order to keep the web balanced, Reed says that the organization has a shared understanding that if one department needs an extra hand, another one will be able to provide it. This inter-organizational attitude enables them to act as one team, thus allowing them to prioritize the well-being of community members.

In addition to online engagement techniques for large surveys as well as small celebrations WFN has been able to host a few distanced events in accordance with provincial health guidelines. One such event was Overdose Awareness Day, during which the community was invited to gather outside at a particular tree. Folks were able to write and hang a tag on the tree to commemorate those who have been lost to overdose. The Chief and Council were central players, and Reed says that they were the ones flipping burgers and distributing food at the barbecue following the event.

“People are present,” she emphasized. “They are super supportive. And it’s not just the Chief and Council, but also the whole community that is coming together and asking what they can do to help.” It’s clear that through this pandemic, all levels of the community have found value in coming together to engage not only on important policy issues like a Childcare Needs Assessment, but also on the sharing of experiences whenever possible.

In the face of large-scale upheaval, Maria sees an abundance of small achievements in WFN. The work for the Child Care Needs assessment continues, and with the strong foundation of community engagement put into place since the start of the pandemic, WFN is well-positioned to gather and lift the voices of community members to create lasting change.

1. Used in some First Nations communities, a Comprehensive Community Plan (CCP) is a “holistic, community-driven planning process that covers all aspects of the community and lays out a vision and goals for the long term.” Visit the Comprehensive Community Planning website for more information.