Scott Lear is a Professor of Health Sciences at Simon Fraser University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article published June 30, 2018.

Heart disease affects approximately 2.4 million Canadian adults aged 20 years and older, and is the second leading cause of death in Canada.

Because February is “Heart Month,” we will see many events throughout Canada and the United States promoting suggestions for improving your heart health — from embracing healthier diets to quitting smoking.

But what about the community that you live in? How does your neighbourhood affect your risk for heart disease?

Most of us can imagine that if we don’t have clean drinking water, heat, hydro or even garbage collection, our health might suffer. But what if we don’t have a sidewalk? Can that really affect our risk for heart disease?

In recent decades, there’s been growing interest in how the built environment (the human-made design and infrastructure of communities) relates to behaviours such as physical inactivity and poor nutrition, and risk factors such as obesity and diabetes — all of which are common determinants for heart disease.

Obesity and your car

Soon after the Second World War, cities began to expand outward as people wanted to live in detached single-family homes. These areas are what we know as the suburbs, and their development continues.

Living in the suburbs removes people from their daily destinations. Getting to work and doing simple shopping errands requires a car. The more time spent in a car, the greater the risk for obesity — as much as six per cent for every hour per day.

These communities are characterized by streets that meander around with many cul-de-sacs and dead ends. This increases distances between destinations from how the crow flies. So a neighbour who is really only 80 metres away becomes 500 metres away, and for many people, that means driving.

The absence of sidewalks in many communities is also a deterrent for walking. We know that in communities with sidewalks, residents are more active than in communities without sidewalks. Even with sidewalks, it is rare to see people out walking as there is nowhere to walk to.

In Niagara Falls, Ont., residential areas are spread out and separated from retail areas. Simple errands like simply picking up some milk require a car. Image provided by author.

While it’s possible to be active in communities that are not walkable, it’s more difficult. More conscious thought and planning needs to go into it. It means purposely talking a walk after you’ve come home, or driving to a gym or other place to get exercise.

This takes more time, and given that lack of time is often suggested as the reason why people aren’t active, we need to minimize as many barriers as possible.

Community design and heart disease

In contrast, communities that are set up in a grid-like street pattern combined with a mix of retail, commercial and residential areas lead to more walking.

In these communities, getting to that neighbour 50 metres away may only entail a 75 metre walk. In addition, there tends to be greater access to public transit, and people who use transit are also more active than non-users.

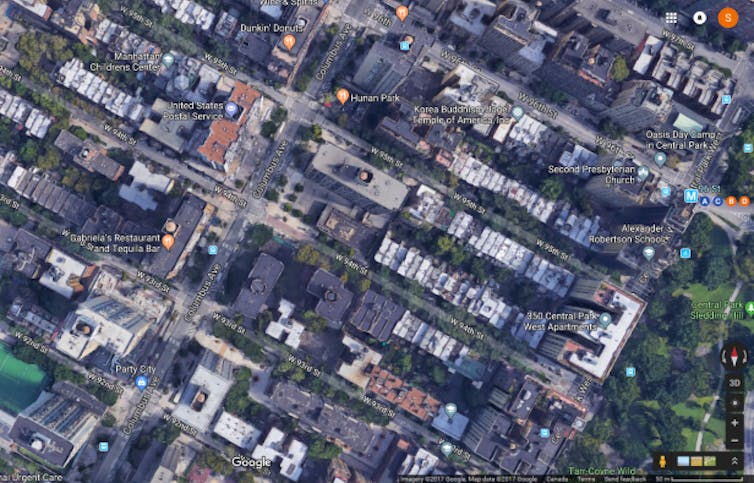

New York City: Stores and other destinations are mixed in with residential homes and streets are also set up in a grid-like pattern, reducing distances between destinations. Image provided by author.

The presence of parks and green space also affects our risk for heart disease. Besides creating an attractive place to walk, run, bike and play sports, having access to green space is associated with lower stress levels and greater well-being.

Taken together, living in these areas has been associated with a lower risk for obesity and diabetes, which in turn lowers one’s risk for heart disease.

But it’s not just our activity levels that the community can affect. Even the type of food outlets in our communities affects our risk for heart disease. In one study in Sweden, people who moved from a community with few fast-food outlets and convenience stores to one with a higher number saw their risk for type 2 diabetes go up significantly.

Do you trust your neighbours?

Places that are more walkable, or have more grocery stores, tend to be wealthier, whereas things like fast-food outlets tend to be more common in poorer areas, which also have less access to parks and community centres.

That makes it hard to know whether it is the physical environment itself or the social structure within that environment that has an impact on heart disease, and it could be both.

A recent study from the southeastern U.S. found a higher risk for heart failure in low-income communities over a five-year period, such that those in the poorest communities had a 36 per cent increased risk compared to the wealthiest.

The authors speculated it’s due in part to less educational and occupational opportunities in the poorer areas, as well as less access to quality health care. The higher risk may also be related to lower neighbourhood cohesion (the amount of trust of others in your community), which has also been associated with increased risk for heart disease.

With these new findings, more and more people are expressing their desire to have walkable communities and many cities are responding by adding in bike lanes, mixing residential and retail areas and even creating little town centres in suburban areas within walking distance.

As cities make these changes, it will be much easier to make the healthy choice — whether walking instead of driving, or eating fresh produce instead of fast food — and therefore help reduce your risk of heart disease.

Scott Lear writes the weekly blog Feel healthy with Dr. Scott Lear.

Author Credit: Scott Lear, Professor of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.